User-defined types

The type Userobject is a place

holder for user defined types . Such types can be used for

defining object-oriented data models. User-defined types are always

surrogate types.

The create type statement creates a new user defined type.

Examples:

create type Person

create type Student under Person

create type Teacher under Person

The result of a create type statement is a surrogate

object representing the so created

type. The new type will be a subtype of all the supertypes in the

under clause. If no supertypes are specified the new type becomes a

subtype immediately under the system type named

Userobject.

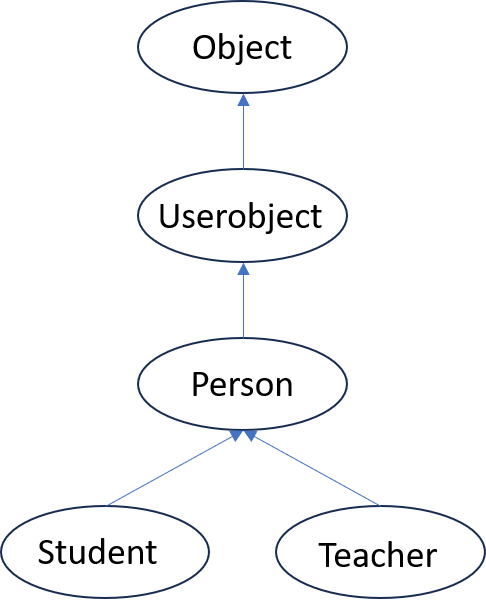

After the type definitions above the type hierarchy around type

Userobject will look like this:

Multiple inheritance is defined by specifying more than one supertype, for example:

create type TA under Student, Teacher

Defining properties

Properties of a type are defined as functions. The simplest kind of

functions are stored

functions,

tabulated in the local database. Let us add the

properties name and income to type Person as stored functions:

create function name(Person p) -> Charstring

as stored

create function income(Person p) -> Real

as stored

Creating user objects

The create statement can be used to populate the database by

creating objects of a given type. Each new objects can

thereby be assigned initial values for specified attributes

(properties).

Example:

create Person (name, income) instances

:venus ("Venus", 3500),

("Serena",3900)

The statement above creates two new user objects of type Person

and binds the session variable :venus

to one of them. It thereby sets values of the stored functions name

and income representing the properties name and income,

respectively.

When the database is populated we can make queries by calling the new stored property functions, for example:

name(:venus)

select name(p), income(p)

from Person p

where income(p) > 3500

A property can be any

updatable OSQL function having the

created type as its only argument, here name() and income(). For

each new object a comma-separated list of initial values for the

specified attributes functions can be specified as in the example.

Each initializer can have an optional associated variable, which will be bound to the new object. The variable name can subsequently be used as a reference to the object.

Example:

create Person(name, income) instances

:pelle ("Per",383)

income(:pelle)

Expressions can be used as initial values.

Example:

create Person (name,income) instances

:kalle ('Kalle ' || 'Persson' , 200*1.5)

name(:kalle)

income(:kalle)

The types of the initial values must match the declared result types of the corresponding functions.

It is possible to specify null for a value when no initialization is

desired for the corresponding function. Bag valued functions are

initialized using the syntax (values e1,...).

Deleting user objects

Objects are deleted from the database with the delete statement.

Example:

delete :pelle

The system will automatically remove the deleted object from all stored functions where it is referenced.

Deleting types

The delete type statement deletes a type and all its subtypes.

Example:

delete type Person

If the deleted type has subtypes they will be deleted as well. In this

case Student, Teacher, and TA and all theirs properties and

objects are deleted.

Example: After deleting type Person the following query fails.

select name(p), income(p)

from Person p

Updates

Information stored in the database is represented as mappings between

arguments and results of functions. These mappings are either defined

at object creation time or altered by one of the function update

statements: set, add, or remove.

The set statement

The set statement sets the value of an stored function for given

arguments.

To illustrate how to use the set statement to populate an

object-oriented data model, assume the following model:

create type Machine;

create function name(Machine) -> Charstring as stored;

create function manufacturer(Machine) -> Charstring as stored;

create type Installation;

create function name(Installation) -> Charstring as stored;

create function machine(Installation) -> Machine as stored;

create function location(Installation) -> Charstring as stored;

Let's create two objects, one object of type Machine and one object

of type Installation bound to the session variables :m1, :i1,

respectively, without setting any of their properties:

create Machine instances :m1;

create Installation instances :i1

Now we can populate the database by setting the properties of the

machine :m1 and the installation :i1 one-by-one:

set name(:m1) = "L90F";

set manufacturer(:m1) = "Volvo";

set name(:i1) = "MiA";

set machine(:i1) = :m1;

set location(:i1) = "Eskilstuna";

We can update the name of installation :i1 to MiB:

set name(:i1) = "MiB"

Test it:

name(:i1)

Notice that the create object statement is

an alternative to setting property values one-by-one with the set

statement.

Example: Let's create another machines :m2 and an installation,

:i2 using the create object rather then the set statement:

create Machine (name, manufacturer) instances

:m2 ("CBM 7000", "Hagglunds");

create Installation (name, machine, location) instances

:i2 ("Cooler", :m2, "Bredbyn");

Let's define a derived function

to retrieve the installations of a machine m.

create function installations(Machine m) -> Bag of Installation

as select i

from Installation i

where machine(i) = m

Test it:

select name(i), location(i)

from Installation i

where i in installations(:m1)

Object properties can also be updates by a set statements with a

query:

Example:

set name(m) = 'CBM 8000'

from Machine m

where name(m) = "CBM 7000"

Here the update retrieves machine m named CBM 7000 and then sets

the name ofm to CBM 8000. Let's test it:

select name(m)

from Machine m

Updatable functions

Not every function is updatable. Stored functions are always updatable. A derived function is upatable only if its body contains a single call to an updatable function with all arguments of the derived function. In particular inverses of stored functions are updatable.

Example: The function installations(Machine)->Bag of Installation

being the inverse of machine(Installation i)->Machine is

updatable. Let's create a new installation :i3 located in Uppsala

without setting its Machine property:

create installation (name, location) instances

:i3 ("Shedder", 'Uppsala');

We can now update the installations of :m2 to be both :i2 and

:i3:

set installations(:m2) = (values :i2, :i3)

Test it:

select name(i), location(i)

from Installation i

where i in installations(:m2)

The add statement

The add statement adds a result object to a bag valued function.

Example: Let's create a new installation :i4

located in Falun:

create Installation (name, location) instances

:i4 ('Mymill', 'Falun');

Now we can add :i4 to the installations of :m2

add installations(:m2) = :i4;

Test it:

select name(i), location(i)

from Installation i

where i in installations(:m2)

The remove statement

The remove statement removes the specified tuple(s) from the result

of an updatable bag valued function.

Example:

remove installations(:m2) = :i2;

Test it:

select name(i), location(i)

from Installation i

where i in installations(:m2)

Updating Boolean functions

Setting the value of a Boolean

function to false means

that the truth value is removed from the extent of the function.

Example: Let's define a stored Boolean function.

create function needs_service(Installation) -> Boolean

as stored;

Let' register that installation :i1 needs service.

set needs_service(:i1) = true;

Let's get those installations that need service:

select name(i)

from Installation i

where needs_service(i)

The following statement registers that installation :i1 has been

serviced:

set needs_service(:i1) = false;

Test it:

select name(i)

from Installation i

where needs_service(i)

Cardinality constraints

A cardinality constraint is a system maintained restriction on the number of allowed occurrences in the database of an argument or result of a stored function. For example, a cardinality constraint can be that there is at most one machine per installation, while a machine may have any number of installation. The cardinality constraints are normally specified by function signatures.

In our example above, the function machine(Installation)->Machine

restricts an installation to be on only one machine, while there may

be many installations on every machine. Therefore the following update

fails:

add machine(:i1) = :m2;

This one fails for the same reason:

set installations(:m2) = installations(:m1);

The system prohibits database updates that violate the cardinality

constraints. For the function machine() an error is raised if one

tries to make an update making the same installation on two machines.

In general one can maintain four kinds of cardinality constraints for a function modeling a relationship between types, many-one, many-many, one-one, and one-many:

One-many is the default when defining a stored function returning a

single value as in machine(Installation)->Machine. There can be one

machine for every installation and many installations for each

machine.

Many-many is specified by prefixing the result type specification of

a stored function with Bag of. In this case there is no cardinality

constraint enforced.

One-one is specified by suffixing a result variable with key.

Example:

create function name(Machine m) -> Charstring nm key

as stored

will guarantee that a machine's name is unique.

One-many is normally represented by an inverse function with

cardinality constraint many-one as for the function

installations(Machine)->Bag of Installation above being the inverse of

machine(Installation)->Machine.

Since inverse functions are updatable the function

installations(Machine)->Bag of Installation is also updatable and

can be used when populating the database.

Any variable in a stored function can be specified as key, which will restrict the updates to maintain key uniqueness.

Cardinality constraints can also be specified for foreign functions, which is important for optimizing queries using the functions. It is then up to the foreign function implementer to guarantee that specified cardinality constraints hold.

Dynamic updates

Sometimes it is necessary to create objects whose types are not known until runtime. Similarly one may wish to update functions without knowing the name of the function until runtime. This is achieved by the following procedural system functions:

createobject(Type t) -> Object

createobject(Charstring tpe) -> Object

deleteobject(Object o) -> Boolean

addfunction(Function f, Vector argl, Vector resl) -> Boolean

remfunction(Function f, Vector argl, Vector resl) -> Boolean

setfunction(Function f, Vector argl, Vector resl) -> Boolean

The function createobject() creates an object of the type specified

by its argument.

The function deleteobject() deletes an object.

The functions setfunction(), addfunction(), and remfunction() update a function given an argument list and a result tuple as vectors. They return true if the update succeeded.

To delete all rows in a stored function fn, use:

dropfunction(Function fn, Integer permanent)->Function

If the parameter permanent is the number one the deletion cannot be

rolled back, which saves space if the extent of the function is large.